Think You’ve Made Your Last Dive?Contents of this Issue: One More Bahamas Boat, the Rorqual What You See When You Dive Deeper Readers Lose Money with Scubacan Think You’ve Made Your Last Dive? Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 let your eternal reef give you one more for etern i t y from the February, 2002 issue of Undercurrent

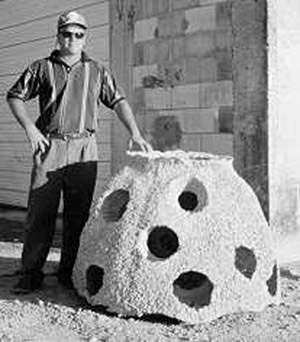

Off Florida’s Longboat Key in Florida, Lynne Lamb Bryant consigned her late husband to the warm, jade-colored waters of the Gulf of Mexico, after having his remains made into oceanfront property. None of us, it has been said, is an island. But a man or woman now can choose to spend the afterlife as part of an artificial reef, designed to be environmentally friendly and serve as a home to fish and other marine life for at least 500 years. What better place for a departed diver? The deceased’s cremated ashes are mixed into concrete. For $850 to $3,200, based on what the customer or survivors request, this concrete is then molded into a “reef ball,” which looks like an igloo with holes. Once dropped to the reef, the dearly departed can sleep eternally with the fishes.

Teary-eyed, Bryant looked on as the 400-pound, 3-foot-high casting into which they had stirred her husband’s ashes during manufacture was lowered by crane from a barge. Thirty feet below the surface, two scuba divers positioned it on the sandy bottom. “Goodbye, Lee,” Bryant said. “ You sleep in the deep.” It is just one of the latest options in the increasingly diverse American way of death. As Baby Boomers die off, a growing number are having their cremated remains launched into space, sprinkled on their favorite golf course green, or incorporated into objects such as duck decoys, shotgun shells, fireworks, paintings and designer glassware. For divers, reef balls, which add posterity, may be replacing an ocean current, which disperses the ashes in the ocean’s infinity. For Bryant, a 53-year-old resident of suburban Houston, an artificial reef was the solution to a problem that had gnawed at her since her second husband, Lee, a Kansas-born architect, died 20 years ago. An avid sailor and scuba diver, Lee Bryant wanted to be buried at sea, she said, but she was told that casting a body into the ocean is illegal. She had him cremated after he died of a stroke, but didn’t feel right about dispersing the ashes on the water. For two decades, she kept the cremated remains in a plastic urn on a shelf, until she learned of the artificial reefs through the Web site www.eternalreefs.com. She drove to the post office and sent off her husband’s ashes by certified mail. A tossing 30-foot tuna boat carried Bryant three miles off Florida’s west coast, where Manatee County officials are building a reef to shelter myriad fish, including grouper, flounder, snapper and kingfish. Bryant had felt uncertain enough about the offbeat burial rites not to mention them to many of her friends in Houston, she said. But after the burial at sea, she was certain she had done the right thing. The reef ball is “really a sculpture. And Lee loved sculpture.” On the water over the burial site, she sprinkled dried flowers she had kept from her husband’s funeral service two decades before. They had been married for just three weeks and four days. Lowered into the Gulf of Mexico at the same time were a concrete casting containing the mingled ashes of a New Jersey couple, joined now in death as they were in life, and a third igloo made in part of the ashes of a Texas woman. Don Brawley, president of Eternal Reefs Inc., of Decatur, GA, read briefly from a speech by President Kennedy that concluded: “We are tied to the ocean, and when we go back to the sea — whether it is to sail or watch it — we are going back from whence we came.” Brawley, 37, a former network programmer, got the idea for the novel type of burial from his father-in-law, a noted Atlanta pianist, composer and arranger. Carleton Glen Palmer, stricken with terminal cancer in the late 1990s, asked for his remains to become a part of a reef ball. Those castings were the brainchild of one of Brawley’s friends, Todd Barber. His Bradenton, Florida-based company has manufactured more than 100,000 of the items to help revive coral reefs in the United States and other countries and to stimulate marine life. “I’d rather spend eternity down there, with all that life and excitement going on, than in a field with dead people,” Brawley remembers the dying Palmer telling him. On May 1, 1998, the first “memorial reef” was cast, incorporating Palmer’s ashes. Like the balls immersed last week, it went into the Gulf off the coast of Sarasota. “I told business acquaintances about it, and they said, ‘ Wow, that’s neat. Can you do this for other people?’” Brawley said. Now his company promotes the reefs as the “only death care option that is truly an environmental contribution and creates a permanent, living memorial for the deceased and their families.” The concrete used is specially designed to withstand the corrosive effects of seawater, according to Eternal Reefs. Once cast, the balls are left in the open air to cure for a month.

Your Eternal Home? The Swiss-cheese holes attract fish, which can seek shelter from storms or predators inside the igloo. The balls’ rough surface allows coral, sponges and algae to adhere and flourish. Brawley has already sunk about 10 0memorial reefs, mostly off Florida, and is negotiating with California authorities to do the same in the Pacific. Eternal Reefs received the green light from the U.S. Government, its founder said, when the Environmental Protection Agency ruled cremation ashes were a permissible “concrete additive.” A customer pays $850 to join a large “community reef” with 100 more people or as much as $3,200 for the solitary glory of the Atlantis, a reef ball weighing 2 tons and Eternal Reefs’ top-of-the-line model. A bronze plaque can be affixed to identify the deceased. Cremation costs are extra. Brawley said that, for him, donning diving gear to visit his late fatherin-law’s reef ball is a joyous experience that brings tears to his eyes. “The best feeling you’re going to get from a cemetery is a somber one, at least for me,” he said. “But when you go to visit a memorial reef and see the fish swimming and all the other sea life, you get a good feeling.” For more information about Eternal Reefs, you may contact them at 1066 Berkeley Road, Avondale Estates, GA. Phone (404)966-7333 or fax (404)966-7337. Their Web site is www.eternalreefs.com. This article originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times, written by John-Thor Dahlburg. Undercurrent takes all responsibility for editorial modifications and additions. |

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.