Browning Pass Hideaway, British ColumbiaContents of this Issue: Browning Pass Hideaway, British Columbia In Search of Undiscovered Diving Zen and the Art of Cageless Shark Diving Saying “No” to South Africa’s Cage Diving Will the Open Circuit Regulator Become Obsolete? PADI Accused of Insurance Fraud That California Real Life Open Water Case Diver Dies: Boat Moves to Next Site without Him Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 profusion of life in majestic yet kooky setting from the November, 2010 issue of Undercurrent

Dear Fellow Diver: A splash of cold water on the face snaps the mind to attention. But surfacing from my first dive after 47 minutes in 50ºF water, my first thoughts had nothing to do with the cold or the currents during the drift from Frank’s Rock to Hideaway Wall. Instead, my brain was bulging with new images. Surfaces were so packed with giant plumose anemones that I could find no place to grab even if I’d wanted to. Many fish looked alien and menacing: quillback and China rockfish looked like giant wasps with dangerouslooking white spikes splayed along their dorsal ridges. Hermit crabs and starfish were so plentiful I stopped taking pictures of them. Closer into the steeply sloped shallows, bull kelp bent with the current.

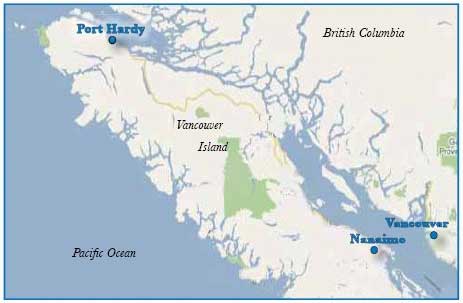

Having never dived these Pacific waters, most of the life was unfamiliar. I learned the names poring over wellused copies of Whelks to Whales and Marine Life of the Pacific Northwest in the dining lodge of one of the most offbeat, and off-the-beaten-track dive “resorts” I’ve seen. This post-dive euphoria was my second rush of the day. The first came after the 4-1/2 hour drive up from Nanaimo to Port Hardy, where we boarded a small launch for the Hideaway. As we approached, I was amazed at the collection of quaint shanties, sheds, and buildings, all floating on giant logs.

The next day, gray whales spouted and surfaced as we headed out to our first dive. Antlered bucks standing no more than knee high (their growth stunted by the lack of forage) peered from shore as we entered the cove where harbor seals cavorted. (Later that week I got an unexpected thrill, throwing a fish to a watchful bald eagle that dove to scoop it out of the water.) As for non-diving activities, forget snorkeling around the lodge; sewage from the toilets deposits into the cove. But after our last dive one afternoon, John treated us to a whale-watching excursion on board his enclosed cruiser, Striker V. We didn’t see whales, but a pod of Dall’s porpoises kept us entertained. Their black and white coloration is similar to the orcas that patrol these waters. Other days, my spouse and I hiked to enjoy spectacular views of neighboring islands across the straits. Diving at the Hideaway means coming prepared, for even simple repairs can be difficult. More than one dive was scrubbed or shortened because a diver’s dry suit zipper or neck seal turned finicky. Bring a save-a-dive kit. Undergarments are hung in your room or draped outside on any available railing; stow drysuits under eaves in case it rains. John explained that in the damp, cool air, our BCs, regulators, masks and fins don’t dry out enough for the salt to crystallize. With the serious water shortage, gear was left strapped on the dive skiff, unrinsed. It took pleading behind John’s back to get staff to break out a second tub for some new guests toting more cameras, and to clean up and freshen the first. I came to have great respect for John deBoeck, who has been guiding divers in the waters for 30 years, first as master of the liveaboard MV Clavella, then since 2003, as the Hideaway owner. He knows how the lighting, tides, current, wind, temperature, and waves affect every site and the marine life. He’s also an inveterate packrat, but with enough of an artist’s eye to keep the flotsam and jetsam he’s found arranged cleverly in plain view, keeping people grinning, even as they cluck their tongues over the floating garbage dumps he’s set up. Though there is no email, phones, or cable TV at the Hideaway, he patiently answers emails whenever he gets back to civilization. Dive times revolved around the tides, changing daily. The dive skiff was tied up to a dock next to fill whips. After first starting one of the camp’s two generators, John turned on the compressor and filled four tanks at a time. Fills on the steel 100 I used ranged between 2700 and 3250. I had to ask John to top off a tank I felt was a bit low only once. John’s website mentions his other boats, some with cabins that presumably would be used in bad weather. In the balmy 50-70ºF days that prevailed in July, we squeezed fully suited up onto a 22-foot-long, 8 foot wide flat bottomed herring skiff powered by a 40HP, donning our belts and tanks en route to the site. This might sound cramped, but it wasn’t. The most we ever had on board was eight. Entry was by backroll. This is not a place for careless practices. Due to the tidal currents, John would usually have to run the motor almost up to the point of pickup. Most climbed up the wobbly portable boarding ladder in full gear; divers could also remove weights and BCs before climbing on board. Apparently, 70-100 foot visibility, better for wide angle work, primarily occurs in the colder months. That we didn’t have more than 20 feet viz meant I could concentrate on macro. Poor viz or not, at Seven Tree Island, I quickly spotted an opalescent nudibranch, its many orange-tipped cetera making it look as shaggy as a yak, while its translucent white body almost glowed. A ruddy scalyhead sculpin clung to the rocks near a vermillion star. I photographed a giant acorn barnacle, its cirri extended like a flower’s pistil. The visibility made it tough to get an entire lumbering Puget Sound king crab in one frame.

Most dives were memorable, but our dives on the SS Themis and Browning Pass Wall stood out, perhaps because I was on a mission: to find one of the wolf eels that haunt the Themis, and to find the giant pacific octopus on Browning Pass Wall. The Themis was a 270-foot freighter that ran onto Crocker Rock in 1906. Laying half between a kelp forest and half on the reef, it ranges from depths of 25 down to 80 feet or so. It’s broken up, but enough nooks and crannies are intact for plenty of marine life to find homes. A fish-eating rose anemone caught my attention; its mouth/anus in the process of either expelling or eating something. Perhaps with its white dagger-like spines, the dark copper and yellow quillback was unafraid to let me near. As I peered into a dark cave of steel, a kelp greenling moseyed past. A lingcod, with its big lips and broad pectoral fins, swam by. Red soft coral dotted the wreckage. A foliate kelp crab waved its white pincers to catch kelp on the current. Back on board, my fellow divers talked about the wolf eels they had seen, one with a head the size of a human’s that looked like a wizened old man. But I got skunked, though when we returned to the Themis at the end of the week, shivers ran up my spine when I was buzzed by a sea lion . . . but no wolf eels again.

John stays on the boat during a dive, and we usually dove without a divemaster, so self-reliance was critical. Groups would become widely separated. Fog was not uncommon; I was glad I brought the best safety sausage (from DAN) and audible signaling device (a Dive Alert Plus) I own. Almost every diver got cold before they ran low on air. Thirty-five-minute dives were not uncommon. I stayed warm enough to dive in the 55-minute range. Under my light “travel” DUI tri-lam, I wore three layers of undergarments: a thin base wicking layer of poly-propylene, mid-weight fleece hunting undergarment, and DUI Powerstretch 300, three layers of PolarTec-type socks, three-fingered dry “lobster mitts” that allowed me to wear the thickest Thinsulate-lined wool gloves that I could find and a 7-mil hood. Those surfacing earlier all wore five-fingered dry gloves, with thinner gloves underneath, and fewer layers of socks. At our three dives on Browning Pass Wall I got a taste of what John called the “best wall dive in the world.” The sheer vertical surface drops to 300 feet. Currents need to be just right for the gentle drift not to become a torrent that sweeps you past the goodies. There is so much life on the wall, starting with a white shag carpet of giant plumose anemone, there are almost no hand-holds. I saw a beautiful orange-peel nudibranch the size of my hand, giant basket stars every 50 feet or so, decorator crabs — perhaps 10 times the size of their Caribbean cousins — and dense patches of hermit crabs. Rockfish were ever present. Orange sea cucumber seemed to burn like little torches, while nearby, icy looking frosted nudibranch crawled along. Here and there, white-spotted rose anemone found a perch. Bright red blood stars, white and orange painted stars, striped sunstars, and rose stars draped themselves everywhere. I got a huge thrill as I captured one fleeting photograph of an elusive ratfish, its splayed pectoral fins translucent and white spotted body clearly standing out, even in waters cloudy with plankton. After our departure, we spent two nights in the beautiful city of Vancouver. En route to our hotel, we got off our ferry at Horseshoe Bay and drove for two hours (including stops to snap photos) up scenic Sea-to-Sky Highway 99 to Whistler, site of many 2010 Winter Olympics ski competitions. The next day we rented bikes and toured Stanley Park. Like San Francisco both in geography and attitude, Vancouver is set on a peninsula. The park is bordered by water; the bike path has spectacular views. Within the park sits the city’s aquarium; I paid the $30 admission to see the giant pacific octopus and wolf eel I missed while at the Hideaway. That the Hideaway at Browning Pass is nestled in some of the most beautiful scenery on the continent adds to its attraction. If you want Galapagos level dive novelty, are comfortable diving in cold water with a profusion of unique sea life, and don’t mind “Uncle John’s” rustic hunting lodge-style accommodations, put Browning Pass Hideaway on your must-experience list. --S.P.

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

From a

distance, it looked like a little village in

the afternoon sun. The charming

facade quickly morphed into

something bordering on downright

kooky behind the scenes (as in

the reality TV show “Hoarders:

Buried Alive”). We stepped

onto the dock with three other

groups also beginning their

stay. Thirty-something Canadian

Christie enthusiastically showed

my spouse and me to our private

“Trapper Cabin,” where a

dingy cloister held a bunk bed,

a mattress tipped on edge and

upended furniture in an adjoining

nonfunctioning bathroom.

Cautiously, I said, “Oh, there’s

been a mistake. John told us we would have a working toilet and shower.” With

a pleasant “No worries,” Christie showed us the “Bunkhouse,” with a cozy living

room with fireplace, a couple of adjoining bunk-bed-filled bedrooms, and a pair

of toilets. The kitchen/dining building (the “Hideaway”) had cubby hole/sleeping

areas separated by draperies from the dining area, with a shared bathroom with

tub and shower. We were relieved when she next showed us the floating two-story

blue clapboard with a shower/toilet on the first floor and toilet on the second.

Its six bedrooms each barely held a twin bed and some shelving, but were clean and

private. My spouse and I picked facing rooms on the first floor, and eased into

our surroundings. With a regional water shortage, nothing said “rustic” quite

like having to fetch a bucket of sea water to flush the indoor toilet.

From a

distance, it looked like a little village in

the afternoon sun. The charming

facade quickly morphed into

something bordering on downright

kooky behind the scenes (as in

the reality TV show “Hoarders:

Buried Alive”). We stepped

onto the dock with three other

groups also beginning their

stay. Thirty-something Canadian

Christie enthusiastically showed

my spouse and me to our private

“Trapper Cabin,” where a

dingy cloister held a bunk bed,

a mattress tipped on edge and

upended furniture in an adjoining

nonfunctioning bathroom.

Cautiously, I said, “Oh, there’s

been a mistake. John told us we would have a working toilet and shower.” With

a pleasant “No worries,” Christie showed us the “Bunkhouse,” with a cozy living

room with fireplace, a couple of adjoining bunk-bed-filled bedrooms, and a pair

of toilets. The kitchen/dining building (the “Hideaway”) had cubby hole/sleeping

areas separated by draperies from the dining area, with a shared bathroom with

tub and shower. We were relieved when she next showed us the floating two-story

blue clapboard with a shower/toilet on the first floor and toilet on the second.

Its six bedrooms each barely held a twin bed and some shelving, but were clean and

private. My spouse and I picked facing rooms on the first floor, and eased into

our surroundings. With a regional water shortage, nothing said “rustic” quite

like having to fetch a bucket of sea water to flush the indoor toilet.

Mealtimes

were communal

affairs. Everyone

sat elbow-toelbow

in a big

U, around pushedtogether

tables, with the food set out in bowls and

platters across from the sink and

stove. Depending on dive times, we

might have a pre-dive light breakfast

of cold cereal, fruit, bread, bagels,

and peanut butter and jelly. The main

breakfast included pancakes or French

toast, bacon, sausage, eggs, and cold

breakfast leftovers. Lunches were

usually sandwich fixings such as a

meat and cheese, with lettuce, tomatoes

and spreads, plus a hearty (the

kind where every ladle is chock full

of noodles, veggies and chunks of

meat) home-made soup. At suppers we

had a tossed salad, two meats, four

vegetables, and a fantastic dessert—

-the cakes Christie baked were outstanding,

especially the carrot cake.

Mealtimes

were communal

affairs. Everyone

sat elbow-toelbow

in a big

U, around pushedtogether

tables, with the food set out in bowls and

platters across from the sink and

stove. Depending on dive times, we

might have a pre-dive light breakfast

of cold cereal, fruit, bread, bagels,

and peanut butter and jelly. The main

breakfast included pancakes or French

toast, bacon, sausage, eggs, and cold

breakfast leftovers. Lunches were

usually sandwich fixings such as a

meat and cheese, with lettuce, tomatoes

and spreads, plus a hearty (the

kind where every ladle is chock full

of noodles, veggies and chunks of

meat) home-made soup. At suppers we

had a tossed salad, two meats, four

vegetables, and a fantastic dessert—

-the cakes Christie baked were outstanding,

especially the carrot cake. Diver’s Compass: The six night dive package, including water transfers to and from

Port Hardy, all meals, and the freedom to open the fridge or cupboards and snack

any time was $1460 for me and $1250 for my non-diving spouse (tax included); see

Diver’s Compass: The six night dive package, including water transfers to and from

Port Hardy, all meals, and the freedom to open the fridge or cupboards and snack

any time was $1460 for me and $1250 for my non-diving spouse (tax included); see