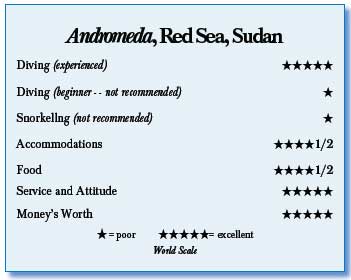

Andromeda, Red Sea, SudanContents of this Issue: Dive Instructor Walks Away Free from Dead Diver Case The Mask-under-the-Chin Syndrome Puerto Morelos, Yucatan, Mexico The Only Way to Get Close to Beluga Whales: Dive Naked Amphibico Shuts Down, Deep-Sixing Buyers and Warranty Holders Litigation: The Dive Industry’s Biggest Threat? Divers Try to Speak “Dolphin-ese” Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 Americans, you’re missing out on fantastic diving from the July, 2011 issue of Undercurrent

Dear Fellow Diver: I'm always looking for the unique, so when I learned that my two buddies and I were the first Americans to make a Sudan trip aboard the Andromeda, I was pleased indeed. Of course, our being first is due largely to Americans' irrational avoidance of the Middle East. In April, just a couple of months after the uprising in Egypt, this luxurious liveaboard was filled with divers from Sudan, Poland, Switzerland, Belgium, Hungary, France, Italy, Russia and Germany. They were embassy personnel stationed in Middle Eastern countries, teachers, lawyers, nurses, doctors, scientists, psychologists and bankers. Ages ranged from 24-year-old twins who had been diving 13 years to 70-year-olds. English was the language of choice, and we 26 became a convivial group. Lively conversations usually centered on mutual interests in food, skiing and the political situation in the Middle East. One older German diver felt so at home that after dives, he changed out of his Speedos on the dive deck. Flashing was the norm as this not-so-shy guy loosely handled his towel.

Five vessels ply the northern and southern Sudan routes, but scores travel Egypt's Red Sea waters. The 130-foot Andromeda is more luxurious than any liveaboard I've taken, and at a great price: $1,442 for eight days and seven nights. She has cabins for 26 divers and 11 crewmembers. Three teak decks provided sun protection and lots of space to veg out alone or be social. Oriental carpets were scattered along the decks. I often slept under the stars on curved, cushioned benches built into the side of the sundeck. The Egyptian part owner (the other owners are Hungarian) has created a spacious Shisha room (think elegant Arabian café) to enjoy flavored tobacco in a water pipe while listening to Arabic music and sipping coffee. He allows passengers to use this stunning area with its oriental carpets, low-slung cushioned couches and colorful leather pillows. I arrived at midnight, thanks to a late flight. I was bone tired after a few hours sleep in two days of traveling but as directed, I set up my dive gear, was issued a Sea Marshal (diver search-and-locate security system) for my buddy team, then crashed, only to take my checkout dive several hours later. I added a kilo more weight than usual because of the higher salinity.

Deep diving found me in deco on most of our 60-minute dives, but that caused no problem because a gradual ascent would simply put me back into a safe no-deco territory. On the northern Sudan site of Angarosh, my two buddies and I were on watch at 140 feet when one started an apparent controlled descent. Watching as she sank lower, I decided to stay close enough to make a dash if she continued descending. At 175 feet, she began to ascend. Whew! We ascended together and headed toward the reef, but I did not see my other buddy. I learned later that she had headed toward shallower depths, but went in the opposite direction, surfaced alone and was picked up by the Zodiac. As we all know, a buddy team of three presents potential problems. When I questioned her, she said she had wanted to go deep but neglected to tell her buddies. Hmmm. Dive sites consist of a plateau, from which we dropped into the blue. The surrounding shallow coral reefs provided ideal spots for safety stops. Tanks (12-liter aluminum and 15-liter steel) were filled in place on the dive deck; nitrox was available but most of us used air because of the deep diving. Two eight-diver Zodiacs with 40-hp engines took us to sites within minutes. Water temperatures at depth were a steady 80 degrees, with air temperatures around 85. A light wind blew on most days. Andromeda's season in Sudan is short, from mid-February to mid-June, because temperatures quickly elevate to 140 degrees in the shade, and well into the 90s in the water. All divers were experienced, a requirement due to the deep diving and strong currents that could change in a breath. We were asked to dive in buddy teams, but that was not enforced. I am accustomed to diving solo but when currents were strong, I stayed close to the others, and we did the safety stop and ascent together. On a few dives, the current was so swift that we had to super-sonic the descent or be swept away. Divers occasionally got swept so far, they chose to be picked up in the blue by the sharp-eyed boat divers. No buddy team member surfaced looking for his partner, as we had made the agreement not to ahead of time. Another "rule" was for buddies to surface with their group of eight and get into the Zodiacs as quickly as possible. That was not an easy task, as handholds on the Zodiacs were limited, so we had to wait for others to hand up weights and BCs. On one dive, six of us were on board waiting for two others, who were floating and chatting. As we drifted close to a reef that came within inches of the surface, the boatman implored them to move quickly, but they ignored his imperatives. When he firmly slapped the rubber and said, "Please come here so I can help you," they shrugged and slowly came to the dinghy. The crew was ever polite, even a few weeks earlier to a group of rowdy Russians who objected to the no-diving-after-drinking rule and pissed on the divemaster's towel. Captain Youssef had firm control of his vessel and crew. After our last day of diving, he oversaw the final mooring, then leaped fully clothed into the water. It was the first time I had seen him laugh and be spontaneous. He swam and played on the mooring ropes, finally beckoning crew members to join him. One day I stopped by the kitchen looking for a snack and he was there scooping up a mixture with a piece of flatbread. He offered me some. Ambrosia! The ingredients -- soft-cooked eggs and yogurt -- belie the flavor. Seeing me scarf it down, Chef Mustafa offered to make it for me for breakfast. Of the 11 crew members, eight were Egyptian and three Sudanese. Remon and Kisha, the two divemasters, stayed with the groups assigned to them. They gave dive briefings in the lounge on a large LCD screen,(the day's schedule was posted on a large board). The dive deck is fine for 26 divers, especially because they are sent in two waves, with only half gearing up at a time. There are hand-held showers on the exit deck and a head on the dive deck. However, there is inadequate space for working on cameras (one must vie with the kitchen crew in the dining area), and no compressed air hose. There are small eight- by six-inch stacked cubbies with 220-volt sockets. The rinse tank for cameras was only suitable for small ones with no strobes. Cabin space was adequate, with a choice of narrow twin (small for anyone broad of beam) or double beds, and a "matrimonial" suite. My main-deck double had two large windows. Bathroom sink and toilets were new, but a pipe leaked in my bathroom so the damp floor had a bit of mold. I took a whiff of the other bathrooms but none had the problem mine did. Chef Mustafa served a variety of tasty dishes with a Middle Eastern flare.

Yogurt with peppermint accompanied every meal. He served an egg dish at breakfast,

such as a frittata or crispy fried egg in a thin pancake batter, with cheeses, tomatoes

and flatbread. Salads abounded at lunch and the 9 p.m. dinners, which were held

after the night dives. The world-class dive on the 500-foot-long Umbria was scheduled for the last day. She lies on her side on Wingate Reef, 20 miles from Port Sudan. As a troop and cargo carrier that was loaded with bombs and weapons to supply Italy's war efforts in East Africa, she was shadowed by the British and ordered to anchor near Port Sudan. After the captain heard that Italy had entered WWII, he scuttled his vessel rather than have it confiscated. (Pioneer diver Hans Hass's written accounts about his dives there are riveting). The bombs' stability was questioned for years; consequently, the public has only been allowed to dive it for the past 15 years. At its deepest, the Umbria sits at 118 feet. My average dives were 45 feet for 80 minutes. Corals adorn her shell. A large barracuda hung like an ornament. Easy penetration in groups of six began inside a room full of wine bottles. We followed the divemaster between steel girders, keeping well off the silted floors. I had to keep close or lose sight of my dive light's reflections on the diver's fins in front of me as the divemaster led us around sharp corners or steeply up or down into holds. Thousands of bombs and detonators had me in awe, as did the huge aircraft tires, thick wire cable, sealed jars and sacks of food, Fiats, giant engines and kitchenware. Wine bottles, all with their corks disintegrated, were in several areas. Much can be seen by entering rooms through a wide entrance from the outside. While everyone aboard was invited to penetrate, a third of the divers chose not to. As an afternoon break, several of us opted for a short ride to Sanganeb Lighthouse, a base for marine science research. Getting to the top of the jetty was tricky, as it involved rock-climbing a vertical 10-foot wall. That, plus the 167 narrow steps to the top of the lighthouse, made for goodly expenditure of energy. But the view from the top was worth it. Several Sudanese live in the lighthouse and maintain it. We then visited Conshelf II, 25 miles northeast of Port Sudan. Seeing where Cousteau blasted his way into the lagoon at Sha'ab Rumi in the early 60s didn't endear me to him, but then it was all for scientific research . . . right? The site itself was carpeted with coral and many fish species. Stark white flower coral in clumps the size of teacups rhythmically opened and closed as they fed. White anemone swayed gently as the anemonefish darted about. Colorful coral adhered to Cousteau's abandoned structures. We took turns going inside the domed underwater garage for his "flying saucer" sledge set on three struts. There was space to surface and look around, but breathing the most likely poisonous air was not recommended. I found the droning sound inside the metal dome intriguing . . . ghosts from the past? Rusted shark observation cages were at 90 feet. While the diving in Sudan is worth every minute and penny of travel, it's a difficult journey. I missed my 10 a.m. Turkish Airlines connection in Istanbul, so had to wait for the midnight flight to Cairo. There is only one flight every week from Cairo to Port Sudan, every Saturday evening. Luckily, I planned to arrive in Cairo the day before. Seats on Sudan Airways were assigned, but that meant nothing, as there was a pushing and shoving rush. Italians were aggressive and engaged in jostling matches with Mulsims in flowing robes. One German couple tried belligerently to oust the Sudanese from their seats to no avail. But the planes are comfortable, with tasty, complete meals served during the two-hour flights. Upon arrival, we waited, jammed together beside the carousel, for our luggage to go through X-ray. If a bag arrived on the carousel with a huge chalk 'X' marked on it, security noted who picked up the bag and ushered them to a Customs hand-check. They look for bottles of liquor and "prurient" materials. A note of warning: Go to the bathroom before checking in for the return flight to Cairo. No water in the airport toilets -- use your imagination. Upon returning to Port Sudan, the beginning of rih al-Khamsin, the 50 days of North Africa's sandstorms, was upon us, creating a hazy mist. Sand infiltrated my every pore. My black dive bag, packed and on the deck, turned gray. I took an optional tour to Suakin, the old medieval port about 30 miles south of Port Sudan. Along both sides of the road, Bedouin encamped in mostly open shanties. Wind whipped sand and the nomads' white long robes billowed. Suakin is largely in rubble, although there is an attempt at restoration where a minaret proudly stands. Blocks of coral were a primary building material, held together with wooden beams and mortar. An old sword salesman was persistent but had no takers. A white-robed and turbaned Sudanese urged on his donkey pulling a cart of branches toward his home across the bridge to the mainland. Planning this trip was a pain. You must have a Yellow Fever inoculation and four facing empty pages in your passport for visas, and you cannot have an Israel entry stamp. Obtaining information from the five liveaboards in Sudanese waters was timeconsuming, so I eventually turned to the dive travel agency Reef & Rainforest, which had never booked this trip before either, to negotiate details. Terrorism in Sudan and the unsettled revolts in the Middle East and North Africa held us hostage about whether or not the trip was a go. Throughout Egypt, dive operators cancelled trips, travel agencies were recommending postponing, and a U.S. State Department travel warning was in effect. We held off making final payment until three weeks before the trip. Andromeda's representative met me at the Cairo airport with my visa and escorted me through Customs to the hotel. Escorts at Sudan's airport were equally helpful. It is a lot extra to pay, but worth it when traveling to Third World countries where Americans are not on the most-favored-people list. But overall, this dive trip was well worth it. And off-gassing for three days in Istanbul wasn't shabby either. -- C.P.

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

Pristine reefs of vivid soft and hard coral graced

the 10 sites we dived, several of them more than once.

I was awestruck to see no broken coral or other evidence

of poor divers. I tried to identify butterflyfish

I had never seen, such as the Oman, orangehead, Red Sea

chevron, masked and Red Sea melon. The masked puffer

got my attention, as did the Red Sea bannerfish, Arabian cleaner wrasse and the bluespotted

ribbontail ray I often saw on the sand beneath table coral. Arabian, royal and

emperor angelfish added even more color. The first three dives (out of four per day)

ranged from 80 to 140 feet. Following the divemaster's lead, I patiently hung at 140

feet, watching distinct shadows of large sharks and hammerheads in the blue -- lots of

them! On day three, as I gradually ascended to 88 feet on Abington Reef, an inquisitive

scalloped hammerhead peeled off from his trajectory three feet away from me. I was

trying to watch but my dive buddy was pointing wildly behind me. I looked up just as

a hammerhead swam over my head. I frequently saw large schools of barracuda, as well

as giant trevally, grouper, jacks, humphead wrasse, bumphead parrotfish and tuna. On

each dive, a few reef sharks cruised by. Triggerfish abounded, particularly red tooth,

clown, orange-lined and the Titan, of which I steered very clear (read why in a story

later on in this issue).

Pristine reefs of vivid soft and hard coral graced

the 10 sites we dived, several of them more than once.

I was awestruck to see no broken coral or other evidence

of poor divers. I tried to identify butterflyfish

I had never seen, such as the Oman, orangehead, Red Sea

chevron, masked and Red Sea melon. The masked puffer

got my attention, as did the Red Sea bannerfish, Arabian cleaner wrasse and the bluespotted

ribbontail ray I often saw on the sand beneath table coral. Arabian, royal and

emperor angelfish added even more color. The first three dives (out of four per day)

ranged from 80 to 140 feet. Following the divemaster's lead, I patiently hung at 140

feet, watching distinct shadows of large sharks and hammerheads in the blue -- lots of

them! On day three, as I gradually ascended to 88 feet on Abington Reef, an inquisitive

scalloped hammerhead peeled off from his trajectory three feet away from me. I was

trying to watch but my dive buddy was pointing wildly behind me. I looked up just as

a hammerhead swam over my head. I frequently saw large schools of barracuda, as well

as giant trevally, grouper, jacks, humphead wrasse, bumphead parrotfish and tuna. On

each dive, a few reef sharks cruised by. Triggerfish abounded, particularly red tooth,

clown, orange-lined and the Titan, of which I steered very clear (read why in a story

later on in this issue). Flavorful potato and rice dishes, roast chicken, beef or

fresh fish, and a soup filled out the dinner menu. One favorite was a baked potato

filled with spicy minced meat. Snacks between the second and third dives included

cakes, yogurt and sliced watermelon.

Soft drinks, powdered juices, coffee

and a variety of teas were available.

Egyptian beer cost a couple

of euro. One could purchase hard

liquor by the bottle. One diver

shelled out 40 euro for a bottle of

mediocre gin.

Flavorful potato and rice dishes, roast chicken, beef or

fresh fish, and a soup filled out the dinner menu. One favorite was a baked potato

filled with spicy minced meat. Snacks between the second and third dives included

cakes, yogurt and sliced watermelon.

Soft drinks, powdered juices, coffee

and a variety of teas were available.

Egyptian beer cost a couple

of euro. One could purchase hard

liquor by the bottle. One diver

shelled out 40 euro for a bottle of

mediocre gin. Divers Compass: My Turkish Airlines from JFK to Cairo via Istanbul

cost $1,140 . . . My eight nights on the Andromeda cost $1,442 . . .

I also bought a package that consisted of Sudan and Egypt visas, the

passport registration fee in Sudan, airport departure taxes, tourism

fees, the cost for a Sudan agent meeting me at the airport, two

nights at a Cairo hotel, round-trip flight from Cairo to Port Sudan,

and ground transportation for $1,159 . . . Somalia pirates often cruise

the Gulf of Aden, at the Red Sea's southern end, but have not attacked

boats in the Red Sea . . . There are travel warnings for the border

between northern and southern Sudan, as the south plans to become an independent

state this month, but Port Sudan is far from that region; still, check the U.S. State

Department website (

Divers Compass: My Turkish Airlines from JFK to Cairo via Istanbul

cost $1,140 . . . My eight nights on the Andromeda cost $1,442 . . .

I also bought a package that consisted of Sudan and Egypt visas, the

passport registration fee in Sudan, airport departure taxes, tourism

fees, the cost for a Sudan agent meeting me at the airport, two

nights at a Cairo hotel, round-trip flight from Cairo to Port Sudan,

and ground transportation for $1,159 . . . Somalia pirates often cruise

the Gulf of Aden, at the Red Sea's southern end, but have not attacked

boats in the Red Sea . . . There are travel warnings for the border

between northern and southern Sudan, as the south plans to become an independent

state this month, but Port Sudan is far from that region; still, check the U.S. State

Department website (