Two Groups of Divers Lost Within a WeekContents of this Issue: Turquoise Bay Resort, Roatan, Honduras Stop Using Zeagle Grace and Zeagle Element BCDs Immediately Reef Sharks Ė Are They Over-Valued? Managing Dive Trip Expectations Consuming Sharks May Drive You Crazy? Two Groups of Divers Lost Within a Week When Youíre Underwater, You Can Become a Client Scientist What Do Fish Know? More Than You Can Ever Imagine Will You Fund a Wrap-Around Mask for Peripheral Vision? Deaths the Result of Too Many Students for One Instructor To Feed or Not to Feed? That is the Question Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 itís every diverís nightmare from the October, 2016 issue of Undercurrent

Coming to the surface and finding you have no boat waiting is probably the most dangerous and frightening circumstance divers can find themselves in. And in the month of September, it happened twice, in different parts of the world, and with different outcomes. On the first day of September, three groups of divers totaling 13 boarded a yacht and journeyed out to Coin de Mire, a group of rocks some distance off the coast of the idyllic Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. They had no idea that earlier that morning, a boat had capsized in rough seas not far from the dive site, killing a baby and a child. A dive guide led each group. Christophe Nadaud, 36, a French national, was in charge of one group, and after entering the water, he decided the strong current and poor visibility made diving untenable and signaled to head back to the surface. Alas, when the divers surfaced, they were astonished to find their boat had departed without them. Evidently, it had gone to drop off the other divers at a dive site with less difficult conditions. It was around 10:15 A.M.

In the group were three Britons, Brian and Julie Byrne, both aged 52, and Jeffrey Tibbles (50) and German national Mary Patricia Vecchio (51). Julie Byrne later told reporters, "Panic set in immediately. The dive leader told everyone to remain calm and started blowing his whistle, saying the boat would hear it and come back. But we quickly realized no one could hear us and the boat wasn't coming back. The instructor was yelling at everyone to swim farther out to sea. It was like the instructor had no safety training. He had no radio, no SOS equipment, no way of calling for help." Though only 50 yards from shore, the guide was concerned the divers might be dashed on the nearby rocks, so he directed them to swim away into the open ocean. The strong tidal currents soon drew them out into the wide-open space of the Indian Ocean. As if the strong current wasn't enough to contend with, the floating divers then endured a tropical deluge that reduced the surface visibility and produced 25-foot-high waves. Jeff Byrne said, "The skies went gray, and it started to rain. It got so dark that we could barely see each other. Even if anything came, it was never going to find us. That was my lowest point." He became sure inquisitive sharks were bumping him. "I got bumped twice quite hard, and it had never happened all throughout the seven hours before," he said. "It was my left leg first and then my right leg. I had my mask, but I thought I didn't want to look down there if there are sharks." As the light began to fade, they began to give up hope of being rescued. Julie Byrne later said, "We thought we were done for, that we'd perish in the water, and our bodies would never be found. We saw a helicopter overhead, and although we yelled and screamed, they couldn't see us." Although Julie was accustomed to dealing with emergencies in her regular job as an ambulance support center operator, she said she was on the verge of breaking down when the helicopter passed over them without apparently seeing them.

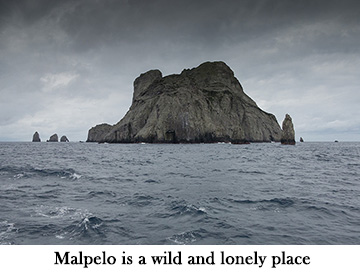

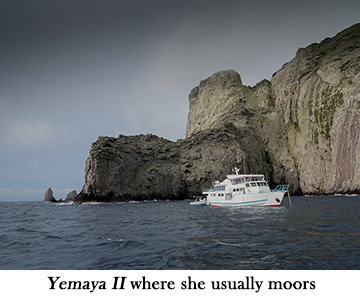

Jeff Byrne added, "Not all five of us would have made it through the night. Three of us were quite strong, two of us not so strong. The German girl got really sick with the heavy seas. She more or less gave in. She was vomiting all the time. She went very quiet." Finally, the crew of a pleasure boat, part of the search group, saw Jeff's large Day-Glo inflated surface marker buoy. The divers were severely dehydrated and sunburned, but otherwise unhurt. "We were all in tears. We were elated," said Julie. "We all just got on the boat, and we were hugging and kissing. Even the two lads who rescued us were in tears. We're just so grateful to everyone who joined the hunt." Stephane de Senneville, director of DiveSail Travel, which contracts out its scuba business to a third-party company, DiveSail Consultants, claims: "The mistake was the decision by the divemaster to swim away from the protection of the cove and into the currents that dragged them out to sea." Pending a full investigation by local authorities, the company has had its license suspended. The divers had their fee for diving waived but little else so far in compensation. Julie Byrne says she is suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. The skipper of the boat and the dive guide were questioned by local police to determine if either was guilty of negligence. But wait, there's more Only one week later, five divers from a Colombian-based liveaboard, MV Maria Patricia, were lost off Malpelo Island when they became separated from their vessel and swept into the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. Malpelo Island is a lonely outpost 320 miles off the coast of Colombia and part of the famed golden triangle for shark-diving enthusiasts, which includes Darwin and Wolf Islands in the Galapagos and Cost Rica's Cocos Island. It's not a trip for the faint-hearted, but subscriber David Marchese (Hummelstown, PA) braved rough seas to visit aboard MV Yemaya II, embarking in Panama, in May. He wrote, "The diving was excellent but on the advanced end. The schools of silkies were impressive, we saw an average of one whale shark each day, and the schools of hammers were pretty thick at times. However, there was a lot of surge, the visibility was poor, and the hammers were more shy than we found them to be in Cocos. This made photography challenging." It was more than challenging in September for Australian Peter Morse, diving from MV Maria Patricia. He was found clinging to the rocky cliff wall nearly 16 hours after starting a dive, by the Panamanian-operated MV Yemaya II . He said later, "They saved my life by being there. I am also afraid that if it were not for them, no one would have raised the alarm about the other four missing divers." He'd been swimming for nearly 14 hours and through the night, unable to get ashore anywhere before finally being washed up on to a rocky ledge. Five divers had originally gone missing from the MV Maria Patricia. Two Colombian divers Jorge Morales and Dario Rodriguez endured a 48-hour drift in the open ocean before being rescued by Colombian naval ship ARC Punta Ardita 39 nautical miles from Malpelo. These two divers later told how they had urinated on each other to keep warm as they huddled together during their ordeal, sometimes curling up in the fetal position while silky sharks circled them. However, it was the numerous Portuguese Men-of-War jellyfish that proved their greatest test, as the two endured continual and intensely painful stings from their long tendrils. Morales said that the first nightfall was the hardest, but it made them realize they had to stick to their survival training, tying themselves together with a buddy-line to avoid being separated. By the second day they were delirious and shivering with cold, even as the sun burned their faces just above the surface and left them dehydrated. "Thinking about our families kept our hope alive." They were finally spotted by a search plane, which dispatched a navy vessel to pick them up. Two other Colombian divers, Erika Vanessa Diaz and Carlos Jimenez, were less fortunate. A body, later confirmed as that of Diaz, the only woman in the group, was later discovered 140 miles southeast of the island, while Jimenez, an experienced instructor who was leading the group, is thought to have perished after a search effort that continued for another four days failed to find him. While the relevant authorities may regulate many liveaboard vessels, you can take your life in your hands if you assume that any vessel abroad is operated safely. When we disappear beneath the surface we abdicate responsibility to those left on board and assume they are keeping a proper lookout for us. Sten Johansson, the dive guide aboard Yemaya II was scathing about the absence of safety procedures of Maria Patricia and the tardy response of the Colombian authorities in effecting a search. Here's his account: Lost Divers at Malpeloa first-hand report by Sten Johansson We arrived as usual after a very windy and bumpy sea crossing from Panama to Malpelo, Colombia.

As soon as we got him onboard, we alerted the Navy and the person in charge of the marine park of Malpelo. When we arrived earlier, our captain reported in to the park ranger and the navy guys stationed on the island, and they said they were busy, and they didn't mention anything about lost divers. However, when we informed that we had found a diver in the water, we suddenly got the news that four other divers were missing, the guide, Carlos Jimenez, a Colombian woman, Erika Vanessa Diaz, and other Colombian nationals Jorge Morales and Dario Rodrigues. They knew we were coming in Yemaya II at dawn because they had the schedule of the boats, so why did they not call us at least 5-7 hours earlier, as soon as they could establish radio contact? Or before that, through our satellite phone, to tell us to keep our eyes open in case the divers had a flashlight? According to Peter, they did not have lights or Nautilus Lifelines with them on the dive. Later, the captain of Maria Patricia said, on the other hand, that they had them onboard, but the divers never brought them on any of their dives... Why not? They started the dive late. The captain of Maria Patricia said later it was all a rush; they entered the water around 4 p.m. They dove outside the main island of Malpelo, at Three Musketeers, specifically by Cathedral, a swim-thru cavern. According to the captain, the current was strong, and the leading southeast wind was also strong at the time. Their skiff was a 4-meter inflatable dinghy with a 15-hp single outboard engine. The dive guide was supposed to be very experienced. He should have canceled the dive and chosen a safer site, especially since it was the last dive of the trip. Worse, the skiff driver was waiting for the divers in an area where he would least expect to find them surfacing. The Maria Patricia was just in front of Three Musketeers, three rocky outcrops to the north of Malpelo, and any responsible captain or crew member would have kept an eye out for the divers on the last dive, in hard weather conditions. Obviously, they did not. Peter was diving with the others, including the guide, with sausages up, drift diving in the blue at a depth of about ten meters. This is common practice in Malpelo when you have a good skiff driver and a good spotter. [Peter Morse later said he didn't understand why their dive guide ,Jimenez, curtailed the dive early because of the strong current, yet made a five-minute safety stop. It transpired later that he had been moving some mooring blocks earlier in the day at more than 165 feet deep and probably needed to make a mandated deco stop.]

Three to four hours later, when Peter was just a few hundred meters away from Maria Patricia, the boat released the mooring and headed out to Three Musketeers, then turned east. They never saw him. He swam to the ramp, where there was a rope ladder to climb on to get to the Navy station, but it was drawn up. He tried to get on the rocks but got shredded by the barnacles. He swam back to the mooring place of Maria Patricia, but there was no boat, so back to the ramp. A big wave eventually washed him up on the rocks, where he managed to hold on and wait for our rescue. He commented, "It was like they did not care -- like they were not looking for us!" The Captain told me he sent out three skiffs to look for the divers. The "biggest" skiff was the four-meter inflatable with a small 15-hp engine... But, Peter never saw any skiffs looking for him. A park ranger told me they sounded the alarm the moment they lost them. So why did they never seek our help until we rescued the first diver? We canceled our diving and started a search pattern from around 8:00 a.m. until dark; we stopped when darkness set in, as according to Peter, no one had a light. If I remember right, we had a plane searching overhead in the late afternoon, but too close to Malpelo. Why were they not here first thing in the morning if the alert was done in the afternoon the day before? Where was the Navy? Malpelo is almost 300 nautical miles from Colombia. If the alarm was raised, why did we not see them until more than 40 hours after the call was sounded?

We received news that the Navy and planes were on their way, so we started to do what we came to Malpelo for: to dive. The Colombian Air Force, U.S. Coast Guard and private planes financed by families and divers in Colombia would be conducting the search and rescue, although I still wondered -- where were you yesterday when it mattered? When we got back on the mother boat after the dive, the captain informed us that we were forced by the Navy to participate in the search and rescue. Our guests had a lot of patience, and everyone pitched in to help. Suddenly we were part of the team, together with two navy boats, the U.S. Coast Guard, Maria Patricia -- to whom we gave a thousand gallons of fuel, oil and water because they were out -- and numerous planes buzzing around. Just before dark, the U.S. Coast Guard plane spotted two live divers in the water. They survived two nights and a day at sea. The plane dispatched an inflatable life raft; the Navy and our boat reached them more or less at the same time. They were brought onboard the navy boat. We knew we should be in the area where the other two divers were found. Three days into the search, Vanessa Diaz's sausage was found. But no diver. If the sausage was found without a reel attached to it, the person who lost it would be upwind and up current, because your sausage would always travel ahead of you unless there was extreme current. But the Colombian Navy kept on with the search pattern planned for the day before. They did not listen, and they did not make any adjustments based on recent events and information that came in. We continued to search blindfolded. I knew where to search. I wasn't sure I would find them, but there was a much bigger chance to find them alive by listening to us old, experienced divers. The two missing divers were never found alive. |

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

Two helicopters, a heavy duty rescue boat, the Coast Guard rescue boat, a Dornier aircraft and a Defender ship had been sent out to search. It was more than seven hours later before they located the divers, more than ten miles from where they had started.

Two helicopters, a heavy duty rescue boat, the Coast Guard rescue boat, a Dornier aircraft and a Defender ship had been sent out to search. It was more than seven hours later before they located the divers, more than ten miles from where they had started. As usual, we tied up on the mooring at Altar de Virginia, a dive site on the northeast side of Malpelo. As it was bumpy on the way in, we had decided to postpone setting up the dive gear. Just when I was on my way to gather our guests for the briefing, a guest asked me, "Who is that in the water?" Our skiff was out there, so I thought it was Juan, my colleague, checking the dive site. It was not Juan. It was Peter Morse, an Australian, a lost diver from the Colombian dive boat Maria Patricia. Lost since around 4:30 p.m. the day before, and it was about 7:30 a.m. when we spotted him...

As usual, we tied up on the mooring at Altar de Virginia, a dive site on the northeast side of Malpelo. As it was bumpy on the way in, we had decided to postpone setting up the dive gear. Just when I was on my way to gather our guests for the briefing, a guest asked me, "Who is that in the water?" Our skiff was out there, so I thought it was Juan, my colleague, checking the dive site. It was not Juan. It was Peter Morse, an Australian, a lost diver from the Colombian dive boat Maria Patricia. Lost since around 4:30 p.m. the day before, and it was about 7:30 a.m. when we spotted him... When they surfaced, they could hardly see the skiff, so they started to swim toward the island and became separated. Peter managed to get to the island after about three hours of swimming hard and ditching his dive tank. Carlos, the guide, would have made it for sure, but sacrificed his life for the Colombian woman and stayed with her, I believe.

When they surfaced, they could hardly see the skiff, so they started to swim toward the island and became separated. Peter managed to get to the island after about three hours of swimming hard and ditching his dive tank. Carlos, the guide, would have made it for sure, but sacrificed his life for the Colombian woman and stayed with her, I believe. That evening the Captain (of Yemaya II) and I went to visit the captain of Maria Patricia. They did not participate in the full-day search for their own lost divers because they didn't have enough fuel to continue the search. [They only carried sufficient fuel for the round trip.] Sailing to a remote destination with insufficient fuel for unforeseen circumstances is beyond stupid.

That evening the Captain (of Yemaya II) and I went to visit the captain of Maria Patricia. They did not participate in the full-day search for their own lost divers because they didn't have enough fuel to continue the search. [They only carried sufficient fuel for the round trip.] Sailing to a remote destination with insufficient fuel for unforeseen circumstances is beyond stupid.