The Potential of a Liveaboard FireContents of this Issue: Aiyanar Beach & Dive Resort, Anilao, Philippines Fiji, Molokai, Little Corn Island, St. Eustatius How You Can Purge Plastic from the Ocean Your Dive Boat Sinks Before You Get There Sharks are Not Pussycats as Shark Divers Discover The Etiquette of Tipping on Dive Trips: Part II Parents Sue PADI over the Death of Their 13-Year-Old Son Failing to Turn Your Tank On All the Way Is “Simply Stupid” The Potential of a Liveaboard Fire New Fire Safety Regulations Coming for US Liveaboards American Diver Dies in Red Sea Aggressor I Fire Those Underwater Photo Courses A DIN or a Yoke Regulator? It’s Time To Know The Difference Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 how to protect yourself from the November, 2019 issue of Undercurrent

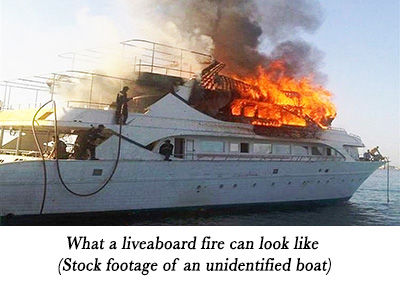

The tragic fire on MV Conception that cost so many lives has all us divers seriously thinking about fire risks on liveaboards -- the accommodations, the exits, the crew preparedness, and our planning. Any vessel can catch fire. In the last few years, we've written about fires on the Egyptian liveaboards MV Blue Melody in August 2014 and on MV Overseas in June 2017 (in which, thankfully, only property was lost). A fire starting in a tumble dryer caused the MV Mandarin Siren to sink in 2012. Then there was the dramatic fire in February 2018 that totally destroyed the luxury liveaboard MV WAOW in Indonesia's Biak Harbor -- luckily, it happened after passengers had disembarked at the trip's end. You can read about all of these in past issues of Undercurrent. While these fires occurred in other countries, the worst fire ever occurred in September in the U.S., even though the Conception had passed the annual Coast Guard inspection in both August 2018 and February 2019. However, an inspection in 2014 cited a leaky fire hose, and a 2016 inspection resulted in Truth Aquatics replacing the heat detector in the galley. The owner resolved the violations. Conception was equipped with a fixed fire-fighting system, as well as various portable extinguishers. However, the boat was built in 1981, and there were no subsequent requirements to upgrade or renew its electrical wiring. The Conception's fiberglass-covered marine-ply hull and superstructure would burn easily, thanks to the waterproofing varnish and layers of glue within it (which, when burning, creates toxic smoke). Many liveaboards worldwide have wooden hulls, although a steel or aluminum hull does little more to protect you from the ravages of a fast-moving fire. MV Royal Emperor had a steel hull, but it went up in flames so quickly after passengers had disembarked at Sharm-el-Sheikh in 2007 that the crew had no time to get their own gear off the boat, including several expensive rebreathers that were on the aft deck. A Fire At Night Is Lethal A fire aboard any boat is frightening, but a fire at night can be lethal. As regular passengers on such vessels, we divers must remember this constantly. If such a tragedy can happen on a U.S.-regulated vessel, what of others elsewhere? After all, we have regulations, but many liveaboards worldwide are not subject to government regulation and scrutiny, and one must trust that the architects designed them properly, that they are equipped with everything required to detect and put out a fire, and that the crew is trained and on watch. And in today's world, that boat and passengers are protected against the potential dangers of lithium batteries. There are various international safety standards for seagoing ships carrying 12 or more passengers, including the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (http://www.imo.org/en). One of the few liveaboards that I can recall travelling on that conformed to SOLAS regulations was MV Royal Evolution, traveling between Port Galib in Egypt and the Sudan. The cruise director did a full safety briefing before setting off, including how to conduct yourself in the life-raft. For example: Did you know you must pass a stool with 24 hours of being in a life-raft or your chances of survival will be reduced? Generally, however, liveaboards are often boats that have been brought into service and converted cheaply enough to do the job. Few meet the standards required to be registered for the international carriage of passengers, so they have limited range and operate only locally. Moreover, owners often pay little more than lip service to fire precautions. For example, most operations ban the charging of cameras and computers while they're out of sight in cabins and expect passengers to leave them charging in the public areas. But who checks? And smoking is reserved to "safe" areas instead of being forbidden entirely. There's always plenty of water to fight a fire but should a major fire occur in vessels that lack internal watertight compartments, seawater fire hoses need to work in conjunction with fully functioning bilge pumps if they are not to jeopardize the boat's buoyancy. Third world liveaboard crews are notorious smokers, and having smokers onboard puts everyone else at risk. Long-time Undercurrent correspondent Fred Turoff (Philadelphia, PA) witnessed a boatman smoking next to an open gas can, but when he mentioned it, the man merely put a cloth over it and carried on smoking. Protecting Yourself on Your Next Boat Trip How can you give yourself a fighting chance of survival during a fire on a liveaboard? Before you book a trip, check the boat's layout, which should be provided by the dive operator on its website. Ensure that there are escape routes leading to both ends of the vessel, and not into the same section. Most liveaboards have the majority of passenger cabins below decks, often with escape routes aft of the engine room or galley -- both areas are potential major sources of fire hazards. When you board, immediately get yourself familiar with these routes, note that they are accessible, and regularly check that they stay unobstructed.

Keep in mind you have a responsibility to do your own homework and pay attention. But do you Undercurrent subscriber Rick Nelson (Discovery Bay, CA) says, "I think many travelers don't pay much attention to the layout or possible hazards in the event of a fire. Having been on many liveaboards, I'm sure we didn't look closely enough at exit scenarios. I do pay attention to the safety briefings, but many people probably don't listen carefully, especially after long travel to reach a remote destination." And, that's a question that may never be resolved about the Conception fire. Did the guests get a proper briefing, did they listen carefully, were there rules for charging electronics, and did they follow them? Bill Pottinger (Berkeley, CA) suggests that a boat should stage a fire drill that actually includes the on-deck muster for all guests (and crew where practical) within two hours of leaving the dock. If your captain doesn't seem to be offering one, ask why. Angelica Litteken (Tavernier, FL) tells how she was on the Emperor Elite in the Red Sea last August when, during the briefing, "the dive leader prohibited charging of any electronics in our quarters to avoid a fire -- and they kept one cabin that was not sealed, so in case of fire, the divers could get out if they could not run up the stairs. But it had a porthole not big enough to escape through." Maybe the fire drill should include every passenger using the emergency escape. No matter how hot and uncomfortable it might get, always sleep with some clothes on. Within easy reach, keep a small grab bag that contains your passport, credit cards, phone, cash, and a waterproof flashlight, which is especially important because it can save your life in the confusion of smoke and darkness. Know where your lifejacket is stowed. These are often kept in the cabins, but the only time I had to abandon ship due to a fire, it was daylight, and the cabins below deck were inaccessible. Steve Holstrom (San Pedro, CA) says he takes precautions, having been on three liveaboards that are no longer floating -- Wave Dancer, Oriental Siren, and Fiji Siren. He says he sleeps with a Spare Air in the cabin and carries a combination CO and smoke alarm. "Of course, these are not necessary if the vessel meets SOLAS requirements." Know that you will be confused if awoken from a deep sleep. Once, when a dive guide knocked on my cabin door in the early hours to tell me a boat anchored nearby was sinking, I presumed it was the early call to dive, so I went to the bathroom instead to take a shower. If it had been our boat going down, I would still be in the bathroom, and that was despite having once survived a sinking freighter in the North Sea and having been a liveaboard dive guide myself. Know where the boat's gas storage tanks are. Liveaboards' galleys often use propane gas (although not the Conception). Heavier than air, if it leaks, it floods downward, with catastrophic results. Gas cylinders should be securely located on the open deck. There would have been therapeutic oxygen on Conception, and some divers may have brought their own oxygen tanks on board for deco dives. Leaking oxygen has dramatic consequences when it meets fire, so never take a personal oxygen-filled deco tank below decks. Get yourself an inexpensive battery-operated combination smoke and carbon dioxide detector. Most liveaboards I've been on have smoke detectors fitted, but there is no reason not to carry your own. Position it as high in your cabin as you can. Never leave a lithium-ion battery charging overnight and unattended, if you can help it. Always disconnect laptops you leave in your cabin or bunk. Ask fellow passengers to do the same. Rick Nelson (Discovery Bay, CA) wrote: "Having used lithium batteries, I am quite aware they can overheat and burst into flame, causing a serious source of a fire, with fuel from the batteries themselves. Larger ones are sometimes charged in closed metal boxes, to prevent flame spread and reducing to a smoldering demise rather than a fire. And today there may also be guests charging larger batteries for drones. Changing technology creates a new set of hazards that must be reviewed and assessed for their impact on overall safety." Know where the fire extinguishers are, and should you discover a fire on-board, don't hesitate to grab one and use it while shouting like hell. Don't be shy if your life depends on this. Finally, there are liveaboards that come in all lengths and configurations, and some divers even take dive trips on chartered sailboats, as did Sandra Maruszak (Meredith, NH) in Guanaja, Honduras, recently. While she had a great trip aboard a crewed 47-foot boat, she tells of a major concern; "They padlocked the hatch at night to make sure no one from outside could gain entrance. I was concerned that in an emergency I would not be able to get out. The key to the lock sat on the counter, but should the key not be found, the only exit was locked, and given how sturdy the hatch door was, I did not think I could break it down manually. The windows were covered with bars (also for security) and there is no other way to get out. In looking back, I should have demanded they use something else to close the hatch (like a 'biner), as I knew what a safety risk it was, but I didn't want to be "difficult." I'm lucky it didn't cost me my life. Most of us don't like speaking up or being difficult, but when it comes to a possible fire hazard, a little spine is essential. -- John Bantin |

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

The pre-departure briefing by the captain or dive manager should not only include what to do if there is a fire, but also it should be made clear that unattended charging of any electronic device in one's cabin is not permitted. And, ask if there is always someone patrolling on night watch.

The pre-departure briefing by the captain or dive manager should not only include what to do if there is a fire, but also it should be made clear that unattended charging of any electronic device in one's cabin is not permitted. And, ask if there is always someone patrolling on night watch.