The Short Cut Mentality in DiversContents of this Issue: Tiburón Explorer; Galápagos Islands, Ecuador Your Trip Reports are the Lifeblood of Undercurrent A Heated Vest, an Essential Cold Water Item Georgia Dive Store Operators Guilty of Bilking the Veteran’s Administration The Caribbean, Palau, Fiji and the Philippines The Apple Watch as a Diving Computer Lack of Progress in Implementing Conception Safety Recommendations Rude Divers Can Ruin Trips (Part II) Electronically Tagging Your Dive Bag so You’ll Know Where it Is Feds Target Companies Involved in U.S. Shark Fin Trade Fishermen versus Divers Comes to a Head in Florida The Short Cut Mentality in Divers Mother and Her Sons Get Left at the Surface Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 a road to disaster from the October, 2022 issue of Undercurrent

In 2020, I listened to a broadcast of a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) meeting in which the board members and committee heads discussed their investigation into the tragic fire aboard the dive boat Conception when 34 divers lost their lives. During the four-plus-hour discussion, they identified several issues contributing to the catastrophic deaths. It was tough to listen to some of the details. During the discussion, the notion of "normalization of deviance" struck a chord with me, and I saw that it had direct application to diving safety. Normalization of deviance means that people become so accustomed to their conscious deviation from a standard procedure that they no longer consider their changes deviant. To them, their changes have become normal operating procedures. During my nearly 50 years as a diving professional and 23 years working at Divers Alert Network (DAN), I have read and reviewed hundred of worldwide diving accident reports. The details of these "accidents" should cause one to reflect on his or her own diving experiences and realize that this could happen to you, just as it did to those highly trained, experienced, and, apparently, qualified divers. Understanding what turned an enjoyable recreational dive into a tragedy is critical if we're to learn how to avoid the same fate. To quote Eleanor Roosevelt, "Learn from the mistakes of others. You can't live long enough to make them all yourself." An Unusual Cause of Diving Accidents In 2008, Dr. Petar Denoble at DAN reviewed nearly 1,000 diver fatalities. He identified triggering events that initiated a cascade of circumstances that transformed an otherwise enjoyable dive into a fatality. Those triggering events were:

Out of Breathing Gas ...... 41%

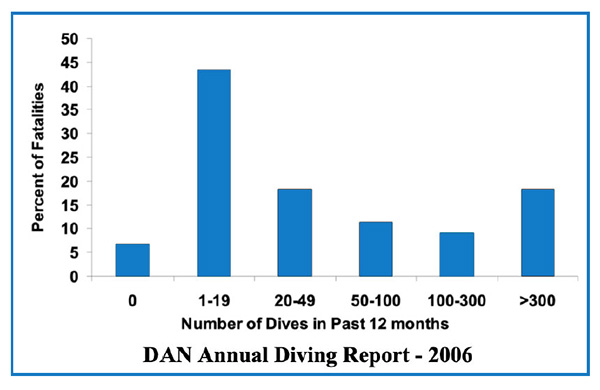

Entrapment...................... 21% Equipment Problems ...... 15% Rough Water..................... 10% Trauma................................ 6% Buoyancy............................. 4% Inappropriate Gas............... 3% More than 60 percent of the identified triggering events (Out of Breathing Gas, Equipment Problems, Buoyancy, and Inappropriate Gas) are directly or indirectly related to equipment preparation and use. However, I think "Equipment Problems" are mainly "Problems with Equipment." In other words, they represent user error rather than an equipment design flaw. Many reports describe a series of actions and habitual behaviors that appear so far beyond comprehension that they defy our definition of "diver error." The problem seems to be that some divers, even those with extensive diving experience, may decide to take shortcuts or deviate from standard safety procedures. They may feel pressure to hurry up, become complacent, or even think that standard procedures may not apply to them. It's Not Just Beginners Who Get In Trouble. DAN's Annual Diving Report has interesting data regarding experience levels for diver fatalities. The graph (below) shows the number of open water dives a diver made during the 12 months preceding death. You will see two distinct spikes in the number of fatalities. One spike involves divers with fewer than 20 open water dives, which might be explained by these divers having limited open water diving experience. Their skills may be insufficient to deal appropriately with a crisis underwater. Another spike shows increased fatalities among divers who made more than 300 open water dives in the 12 months preceding their death. It seems incredible that divers with that much recent experience would get into a situation that initiated a series of events from which they could not recover. How could their skills, abilities, or equipment be inadequate to survive an underwater diving emergency? One explanation could be that they had deviated from standard safety procedures so often that their deviations became "normalized" in their minds because, previously, nothing occurred to alert them to problems with their shortcuts. Divers with extensive experience may believe there is no need to follow all the standard steps to prepare for a dive because they've done it so often that they can deal with anything that may happen underwater. From the accident data, it is undoubtedly true that experience alone does not prevent accidents. Regardless of their experience, all divers should follow all the steps necessary to prepare themselves, their equipment, and their companions for any diving situation.

The experienced divers who died were capable of following proper diving procedures and had done so previously. While "complacency" contributes to diving accidents, "normalization of deviance" may be just as important: divers become so accustomed to a conscious deviation from standard safety procedures that they increase their risk by no longer realizing that their procedures depart from the norm. Even to others with whom they regularly dive, their incorrect methods might seem like a normal part of the divers' approach. When one deviates, and the outcome is successful, without negative consequences, it subliminally reinforces the continuing use of that deviation. In other words, because it worked, the diver may experience a subconscious reward for doing the wrong thing. What Divers Can Learn from NASA? Columbia University sociologist Dr. Diane Vaughn coined the term "normalization of deviance" in her book, The Challenger Launch Decision. In describing the decisions made by NASA that led to the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986, she noted there had been problems with the "O" rings in the solid rocket boosters on previous launches, but without incident. Therefore, it became "normal operating procedure" to make launch "Go" decisions, even though "O" ring issues had been identified. NASA, unfortunately, did not learn from the Challenger disaster and fell victim to it again in 2003, when the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated after the heat shield failed upon re-entry. Apparently, there had been heat shield issues during previous re-entries without incident, so, again, the problems were considered within "normal" operating parameters. To learn from these space flight tragedies and catastrophic incidents within the diving world, we should understand the dangers of deviating from safe operating procedures when they become "normalized." The first step in avoiding the "normalization of deviance" is awareness. In diving safety, we discuss "situational awareness," where we constantly monitor ourselves and our situation as we prepare for a dive, during, and after, always looking for changes that could increase our or our companion's risk. Many factors may increase the likelihood of normalization of deviance. Some divers, even those with lots of experience, develop shortcuts while neglecting standard safety procedures. Their justification is often because they perceive the rule or standard as ineffectual. For example, in boat diving, the pressure to get dressed and get into the water quickly may justify their skipping a few "inconsequential" steps. It may seem right when others are waiting for you, but it will be foolish if things go terribly wrong during your dive. Two simple examples of "inconsequential steps" that get skipped are: not testing the power inflator on your BCD before diving to assure that it is attached to the low-pressure hose properly and not breathing from your second stage while looking at your submersible pressure gauge to ensure your cylinder valve is fully open. Divers may learn to deviate without actually realizing it. Diver training only covers part of what a diver needs to know, so divers may adopt modifications from observing more experienced divers who have procedures that have worked for them. They may do this without questioning or thoroughly evaluating these modifications. My philosophy is to question everything, especially regarding your safety. Just because you see someone else do something, it doesn't mean it is the right thing to do. We dive in a culture that often permits mistakes to go uncorrected. Diving companions may be reluctant or afraid to speak up when they see a pre-dive preparation that deviates from standard procedures. Though we may not be our brother's keeper, we are obligated by common decency to keep our diving companions safe by identifying anything that doesn't seem right. That is another reason to question everything. There is a popular contemporary saying, "See something, say something." By doing so, you may help prevent an accident. Rather than trying to tell someone something is out of whack, point it out to someone with more expertise. Or perhaps you may find it easier to ask a question. "You know, I've never seen equipment configured like that. I have always configured my equipment like this. Can you tell me how this method works?" You can also be more direct, "Do you know your air is off?" "Are you not taking your SMB on this dive?" It's a simple way to bring an error to the attention of a fellow diver, and you may prevent an accident. Never take anything at face value when it comes to diving safety. Resisting the tendency to deviate from standard procedures requires every diver to follow the skills, techniques, and procedures they were taught. Creating the appropriate culture of diving safety requires everyone to participate. All divers must commit to personal responsibility for safety; observe and communicate safety concerns as soon as they are identified; learn from past mistakes and the mistakes of others; apply safe behaviors based upon lessons learned. The Pressure to Hurry The pressure to "hurry up" (also known as "time pressure") is a significant cause of dive preparation errors. Time pressure may cause a diver arriving late to dive to skip important procedures. Or, a diver's companion may dress faster than they do, so the tardy diver tries to "catch up" by skipping critical steps in preparation or even cause the buddy group to forgo essential pre-dive checks simply in the name of expediency. Taking whatever time is necessary to prepare fully will reduce stress, reduce the possibility of making a critical error in pre-dive preparation and increase the enjoyment of the dive. The Importance of Checklists One diving accident worth reporting involves a closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) diver who was discussing CCR diving at a diving event. He boasted about his superior skills and that his equipment preparation was intuitive, so he no longer used a checklist. The next morning, as the other divers followed their checklists as they prepared for the morning dive, they noticed this diver motionless in shallow water just offshore. They jumped in, brought him to the surface, and were able to revive their non-breathing, and very lucky, companion. After inspecting his CCR, they discovered that he had failed to open the oxygen cylinder and had passed out due to hypoxia. It was a lesson learned that checklists are vital to safe and complete pre-dive equipment preparation. To address closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) accidents, the technical diving community gathered in 2012 at Rebreather Forum 3.0 to develop safety recommendations. One recommendation was to use checklists to reduce the likelihood of missing a critical aspect of pre-dive preparation. Unfortunately, diving accident data and post-accident diver interviews show that checklists may not be part of many divers' safety procedures. Using a checklist could have prevented a tragedy in several cases, but many divers don't think using a pre-dive checklist is an essential and standard operating procedure. I believe using a consistent pre-dive ritual for equipment preparation is critical. Getting into a strict routine will help prevent equipment configuration and preparation errors. We all want to enjoy the wonders of diving without ending up as a DAN statistic. Normalizing shortcuts as a regular practice can compromise our safety and the safety of our diving companions. Stick to the proper procedures, and don't risk taking away your most precious gift, life. Diver safety is, after all, no accident! Author Dan Orr, a past president of DAN, has written more than 100 books and articles on diving and diving safety. Dan is a member of the diving industry Hall of Fame and the International Divers Hall of Fame. He and his wife Betty, one of the first members of the Woman Divers Hall of Fame, now operate Dan Orr Consulting, providing a variety of services to the diving industry. References: Orr, Dan, and Douglas, Eric. Scuba Diving Safety. Best Publishing Company. 2007 Orr, Dan, and Orr, Betty. 101 Tips for Recreational Scuba Divers. WiseDivers.com. 2021 Orr, Dan. Time to Return to Diving - But Cautiously. DiveNewsWire. March 29, 2021 Vaughn, Diane, Ph.D. The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA. 1996. Denoble, P., et al., Causes of Recreational Diving Fatalities. UHM 2008, Vol. 35, No. 6 Annual Diving Report. Divers Alert Network. 2006. |

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.