Women Divers and Their Menstrual CyclesContents of this Issue: How to Go Diving with Nondiving Kids New Luggage Limits Slam Traveling Divers Women Divers and Their Menstrual Cycles Unlucky Fiji Divers Poisoned by Dinner Dive Stores, the Internet and the Industry, Part IV Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 studies support relationship with DCI and other diving problems from the August, 2006 issue of Undercurrent

Over the years there has been a huge debate and controversy regarding women and decompression illness (DCI). Many articles have been published in diving journals, presentations made at conferences, and anyone trawling the Net will find even more opinion — some from well-informed authors, but many by “cocktail party scientists.” What is the current state of play regarding our knowledge of women and DCI? Since the 1970s, controversy has centred on the possible relationship between DCI and the time or phase in the menstrual cycle. Although many nondiving studies compare the effect of the menstrual cycle and sporting performance, few investigate DCI and the menstrual cycle. However, studies over a span of 18 years, from both past and prospective records (observing things as they happen) from aerospace and diving environments and from military and civilian disciplines, have had consistent conclusions. They suggest a possible risk of DCI or other problems while diving at different times over a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. Three studies, all different but with similar conclusions, have been published in the last three years. The first study (Lee 2003) looked at the records of women who had been treated for diving DCI in recompression chambers all over the world. Lee found many more reports of physician-diagnosed-and-treated DCI at the beginning and end of the menstrual cycle, with the fewest number of DCI cases in the third week of a typical 28-day cycle. The second study (Webb 2003), from aerospace research, found a greater incidence of altitude DCI at the beginning of the menstrual cycle, with the risk decreasing after the first week. The third and largest study (St. Leger-Dowse M, Gunby A, Moncad R, Fife C, Morsman J, Bryson P) of its kind was published this year in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The work was carried out by the UK-based charity, the Diving Diseases Research Centre (DDRC), which, for 25 years, has been conducting research on the effects of the undersea environment on humans. One project has involved collecting female-specific data from recreational divers for the past 16 years, starting with a comparative study between men and women divers in the early 1990s. In this latest study (I headed up the research team) a large number of female recreational scuba divers kept diving and menstrual diaries for up to three consecutive years. This was a Herculean task started in the 1990s and designed to study any interaction between reported problems during diving (RPDD) and the day in a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. Five hundred and seventy women took part, with 61 percent returning diaries for the full three consecutive years. More than 50,000 dives with more than 11,000 menstrual cycles were recorded, making this the largest study of its kind.

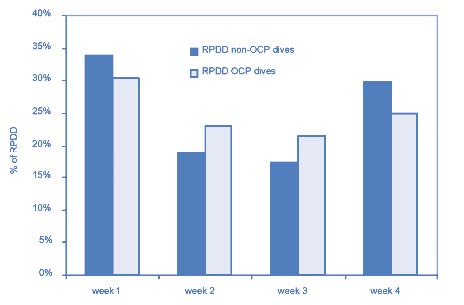

Figure 1 Sixty five per cent of women reported at least one problem during diving, including an inability to cope with equipment; feeling colder than usual; inablilty to control buoyancy; symptoms of DCI; feeling unwell; and an inability to cope with low visibility. Additionally, there were reports of feelings of nitrogen narcosis, inability to clear ears, and feelings of uncertainty and panic. Because of the way the data from the diaries were gathered, we knew the time in every single menstrual cycle of every single dive, and therefore we knew the time in the cycle of every reported diving problem. The diving had taken place evenly over the menstrual cycles, so one would expect the reported problems to be distributed evenly, as well. So imagine our interest when we divided up a typical 28-day cycle into four weeks (week one being days one to seven and so on) and found many more reported problems in most categories in weeks one and four of the menstrual cycle (see Figure 1). This proved to be statistically significant. Of particular interest were the data regarding problems with equipment. One would expect these to be reported evenly and to be a rare occurrence given the reliability of dive gear. But there were many more occurrences of equipment problems in week four than would be expected, suggesting that some reports may be due to judgement or procedural errors. There were also more reports of feeling cold and an inability to control buoyancy in week one. We also knew whether the women were taking an oral contraceptive pill (OCP). However, the issue regarding whether there was more risk attached if one were taking the pill was less clear. It may depend on whether women were extending their cycles for social reasons (that is, continuing to take the pill to avoid a bleed) or what type of pill they were taking. Though this study was not looking at DCI and the menstrual cycle per se, the trends of reported problems during diving were similar. The mechanism for these and the DCI findings is unclear, but researchers believe that it may be hormone fluctuation–related. Table 1

Of course, this study and the others have been based on self-reporting by divers or trawling through past records. Researchers now need to conduct a physiological study to investigate in a more scientific way exactly what is happening and why. ••••• Author Marguerite St. Leger-Dowse has been associated with the Diving Diseases Research Centre (DDRC) in Plymouth (UK) since 1989, where she initiated the first study “Men and Women in Diving.” As a research coordinator, she launched the second phase “Women in Diving,” in 1996 — the largest female-specific sport study ever conducted — which was published in 2006. Other studies include diving and pregnancy, diving and diabetes, diving and asthma, and reverse dive profiles. She has presented at numerous international conferences and contributes regularly to UK diving journals. She is a member of the Women’s Hall of Fame of Diving. Undercurrent asked her if she could be make recommendations for women divers and she replied: “DDRC do not really give out recommendations. However, if a woman feels well and in control, then it is up to her to make the decision whether to dive. She should decide based on what she knows regarding current research, what she feels, and discussion with her dive instructor or buddy. As you can see from the literature, most of the data are ‘record’ based or self-reporting and we need more ‘hard science’ before any official recommendations regarding diving and the menstrual cycle can be made.” |

||||||||||||||||||

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.